Growing up I was always fascinated by nature, but mainly with things you could catch, like butterflies, frogs, and fish. I spent a lot of time biking in the mountains behind my house, but never thought much about what animals might be lurking there. While visiting family a few years back, I started putting camera traps out in the woods I’d spent so much time in as a kid. What I found blew my mind: the forests were teaming with wildlife. Not only were there common species like black bear and gray fox, but my cameras also captured rare species like ringtail cat and Pacific fisher.

I was just home for an extended Thanksgiving/camera trapping extravaganza. When you have a short time to camera trap; you gotta put out as many cameras as possible. I went ahead and brought my entire fleet; all 5 of them. That added up to about 150 lb. of gear.

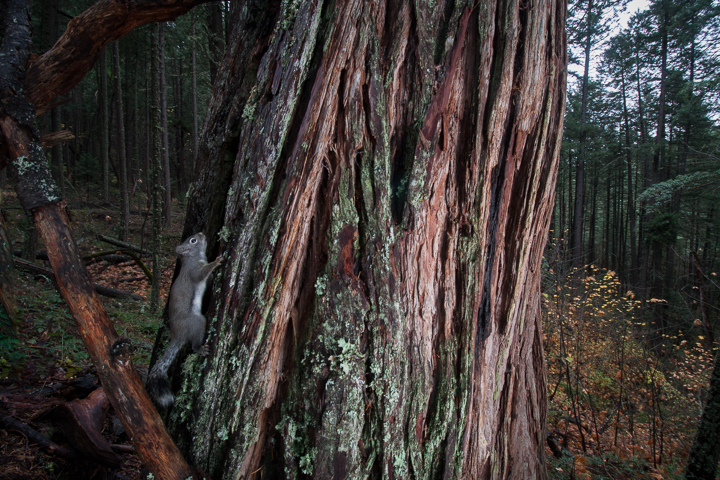

A friend of mine has spent 30 years restoring a 400 acre property that was formerly logged and mined. This amazing chunk of land is all I camera trap when I’m home. The rugged topography and range in elevation provide a variety of habitats to target. There are dry, sun exposed hillsides dominated by manzanita and oak, as well as lush draws with old growth incense cedar and Douglas fir. My goal on this trip was to capture environmental portraits of Pacific fisher. I wanted to showcase not only the animals themselves, but also the low elevation forests that support them.

My camera trapping got off to a slow start. First, this little guy his buddies chewed through the wires at three of my sets.

I soldered the many segments of wire back together and added some conduit for protection. That slowed the squirrels down, but then a new problem popped up; it rained about an inch and a strong inversion set in, leaving my sets under a layer of dense fog. This made for some beautiful conditions in the forest, but led to heavy condensation on all my gear, rendering it pretty much useless.

To add to my troubles, on one of these foggy mornings I had a visitor rearrange one of my sets for me, ruining some of my lighting gear.

I kept my hopes up because I knew there were fishers around. While scouting for sites to photograph, I found fresh scat on several travel routes along streams and on logs spanning draws. I also got one on a game camera I set out on the leaning madrone pictured earlier. The trail camera video reminded me of why it’s so fun to camera trap fishers-they are full of personality.

Finally the fisher shots started rolling in. My first shot came from a set I placed on an old growth cedar. I think of fisher as a semi-arboreal animal that thrives in old growth forests, so I wanted a shot of one climbing around on an ancient tree. This massive cedar fit the bill nicely, I was really taken by the lichen on the bark. Lighting and composing a subject perched on a giant cylinder was far more challenging than I had anticipated. I was thrilled with the shots I got, but I’m also looking forward to trying this again, perhaps with marten in Wyoming.

One of my favorite shots from the trip came on an old madrone log spanning a draw. My fiancee Jessi picked the spot. I strapped a wall plate with a 5/8 ” receiver to the log and mounted my camera to it with a Magic Arm. This set was a nightmare to keep running, the damp draw fogged up my housing half the nights it was out, and the squirrels in the area were especially fond of my flash synch wires. One day I checked the set to find that the arm had slipped and bent straight. When I checked my camera, I saw that the fisher had came through after the arm slipped; I was pretty frustrated.

Then I got a nice surprise as I scrolled backwards through the images: the camera suddenly snapped back into the position I’d set it in and there were some great poses from the fisher. My Magic Arm had indeed slipped, but only because the fisher had climbed onto the housing.

Though my local fishers seem to be doing well, the Pacific fisher was recently proposed for listing as a threatened species. The fragmented populations that remain are suffering from rodenticides used in illegal marijuana farms.

Richarddor - louis vuitton outlet

louis vuitton outlet

louis vuitton outlet

louis vuitton outlet

louis vuitton outlet

michael kors outlet

NIKE AIR

nike air jordan

nike air jordan

jonny5armstrong@gmail.com - My favorite comment so far on my blog:)